Greens and FDP emerge as kingmakers in bid to succeed Merkel

German election updates

Sign up to myFT Daily Digest to be the first to know about German election news.

In previous elections, Germany’s main parties, the Social Democrats and Christian Democratic Union, decided who would govern Europe’s largest economy. This time, the initiative lies with the country’s new kingmakers.

The Greens and the liberal Free Democrats (FDP) could ultimately determine the shape of Germany’s first post-Merkel government and whether it will be led by the SPD or the CDU and its Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union.

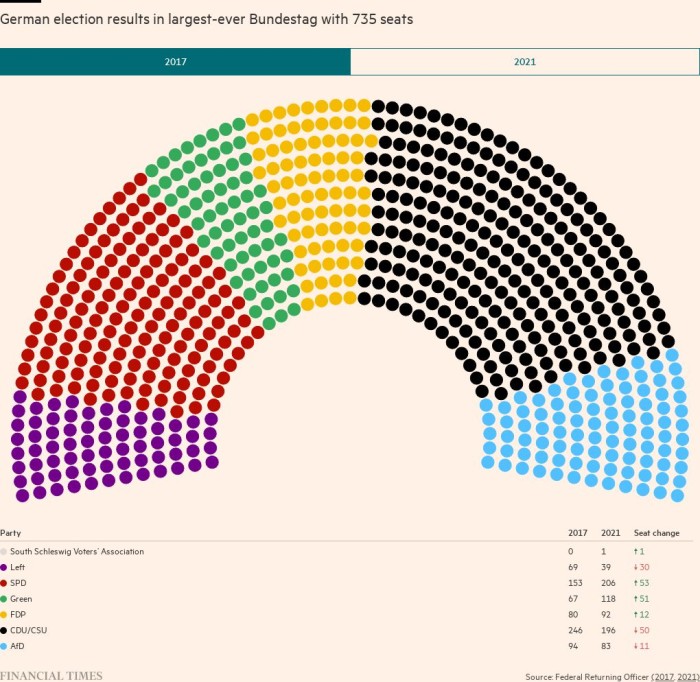

The SPD were the clear winners of Sunday’s election, garnering 25.7 per cent of the vote, a big improvement on the 20.5 per cent they won in the previous Bundestag election four years ago. The CDU/CSU fell to 24.1 per cent, down eight points on 2017 and the worst result in its history.

The Greens had a disappointing night, garnering 14.8 per cent, compared with the 20 per cent or more that many in the party had hoped for, while the Free Democrats (FDP) won 11.5 per cent.

But taken together the two smaller parties won more than each of the once dominant Volksparteien or “people’s parties” — the SPD and CDU/CSU. And it is now the FDP and Greens that will play the key role in deciding who succeeds Angela Merkel as Germany’s chancellor.

“All eyes will now be on the Greens and the FDP — they will decide everything,” Karl-Rudolf Korte, a political scientist at Duisburg-Essen university, told German television on Sunday evening. “Both are now in a position to seek a majority for themselves — will it be SPD or CDU?”

The SPD, winner of the popular vote, believes its candidate Olaf Scholz, finance minister, won a more convincing mandate to form the next government than the CDU/CSU.

But Armin Laschet of the CDU/CSU made clear on Sunday night that he still thinks he has a right to lead negotiations on a new coalition. “[In Germany] it was not always the parties that came in first place who provided the chancellor,” he said, speaking in the “elephant round”, a traditional election-night Q&A session on national TV.

With two men vying for Germany’s top job and the loser effectively refusing to concede, the country is entering uncharted territory — as Laschet acknowledged. “There has seldom been a situation on election night . . . when it wasn’t clear who would be chancellor,” he said. “All Europe is watching what will happen in Germany.”

Difficult coalition negotiations lie ahead, with the threat that Berlin could meanwhile enter a state of semi-paralysis, as it did during the protracted talks that followed the 2017 election, when it took nearly six months for Merkel to form her fourth and final government. But this would come at a time when Germany badly needs to plan its recovery from the coronavirus crisis and prepare for its presidency of the G7 in 2022.

There are two options for a coalition that could command a majority in the Bundestag — in the absence of a repeated “grand coalition” between SPD and CDU/CSU, which neither party wants.

The Greens and FDP could join the CDU/CSU in a “Jamaica” alliance — so called because their green, yellow and black party colours match those of the Jamaican flag. Alternatively, they could join the SPD, whose party colour is red, in a “traffic-light” coalition.

Christian Lindner, the FDP leader, was at pains to stress his party’s newfound strategic importance and the decline of the Volksparteien.

“Neither of the old big-tent parties got more than 25-26 per cent,” Lindner said at Sunday night’s Q&A. “About 75 per cent of Germans did not choose the party that will supply the next chancellor.”

For that reason, he said, it would be “advisable” for the FDP and Greens — two parties united by their desire to overcome the old political status quo — to talk with each other first before they consulted with the SPD and CDU/CSU.

Anton Hofreiter, a senior Green MP, said a “very small group” of FDP and Green leaders would meet soon to see if they could iron out their differences. “We have to find out what we have in common, and what the other side needs for this to work,” he told German radio.

But he warned that the two could not just aim for a “lowest common denominator” set of policies on which both parties could agree.

“It’s completely clear that the next decade has to be a decade of investment,” he said, stressing the need to modernise the German state and fulfil the country’s commitments under the Paris climate accord.

Whatever happens, it will be a difficult dance. Lindner, who opposes tax increases and any changes to Germany’s cap on new borrowing, has made it clear that he sees the “most policy overlap” with the CDU/CSU. He has also made no secret of his warm personal relationship with Laschet: the two, who have known each other for 10 years, knitted together a CDU/CSU-FDP coalition in their home state of North Rhine-Westphalia in 2017.

Meanwhile, the Greens and SPD both want to raise taxes and unleash billions of euros in new investments, and have emphasised that they see themselves as ideal partners.

With big differences to overcome, the coalition talks are likely to drag on for weeks. There is already speculation that Merkel will have to remain as acting chancellor into 2022 — though Scholz said on Sunday night that it was his “ambition” to form a new government sooner “so that Ms Merkel doesn’t have to give yet another [New Year’s] address”.

“We must do everything to ensure that we’re finished by Christmas,” he added. But even if Merkel does not have to wish her fellow Germans a happy new year one final time, it is not entirely clear who will.

Join FT journalists on October 4 for a subscriber-only webinar on the outcome of Germany’s election and its implications for Germany and the rest of the world. Register free at ft.com/germanwebinar

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.