Grammy winner Sinéad O’Connor has died

Irish singer-songwriter Sinéad O’Connor, who shot to fame in 1990 with a shaved head and the Prince-written hit “Nothing Compares 2 U,” then cemented her place in pop culture by shredding a picture of the pope on “Saturday Night Live,” has died.

The death of the soulful, complicated star, whose mental health struggles often eclipsed her art, was announced in a family statement Wednesday issued to the BBC. She was 56.

“It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of our beloved Sinéad. Her family and friends are devastated and have requested privacy at this very difficult time,” the statement said. No cause of death was given.

Representatives for O’Connor did not immediately respond Wednesday to The Times’ requests for confirmation.

During her reign in the early 1990s, the artist positioned herself at the forefront of cultural scandals, frequently lamenting growing up in Ireland’s “theocracy” and abuses in the Catholic Church. She shaved her head to defy expectations about female sexuality and her stormy relationships with Irish journalist John Waters and drummer John Reynolds provided tabloid fodder.

But it was her infamous “SNL” appearance in 1992 that cast the longest shadow over her career.

While performing a haunting a capella rendition of Bob Marley’s once-banned “War,” she began tearing up a picture of Pope John Paul II on camera. She called on viewers to “fight the real enemy” and urged them to combat child abuse. She became a pariah with the stunt, incurring the wrath of the church, its patrons and even her longtime foil, Madonna.

The artist never apologized.

Sinéad O’Connor performs on Italian TV in 2014.

(Antonio Calanni / Associated Press)

“I come from a tradition of Irish artists where I am principally concerned with affecting my society,” O’Connor told The Times in 2012. “Artists are supposed to act as an emergency fire service when it comes to spiritual conflict — not preaching or telling people what to do but being a little light that tells us that there is a spirit world.”

O’Connor’s contrarian views took root long before the “SNL” performance. She previously backed out of a 1990 appearance on the show in protest of guest host Andrew Dice Clay’s misogynistic stand-up comedy.

“It would be nonsensical of ‘Saturday Night Live’ to expect a woman to perform songs about a woman’s experience after a monologue by Andrew Dice Clay,” she said in a prepared statement.

She later refused to perform at a New Jersey venue if the American national anthem was played and boycotted the Grammy Award ceremonies in 1991, saying the pop world was too materialistic. She was up for four awards that year. Her sophomore album, “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got,” won alternative music performance.

She continued to make outlandish statements, only backpedaling occasionally. In 2000, for instance, she proclaimed herself a lesbian and then — five years later — explained that she was actually “three-quarters heterosexual, a quarter gay.” Then, following her vociferous critiques of the church, she was ordained a priest by a small renegade sect in Ireland that coincided with the release of her 2000 hymnal album “Faith and Courage.”

In 2010, when the church’s sexual abuse scandal hit a pitch, O’Connor said that she still identified as Catholic.

“I’m a Catholic, and I love God. … That’s why I object to what these people are doing to the religion that I was born into,” she told The Times.

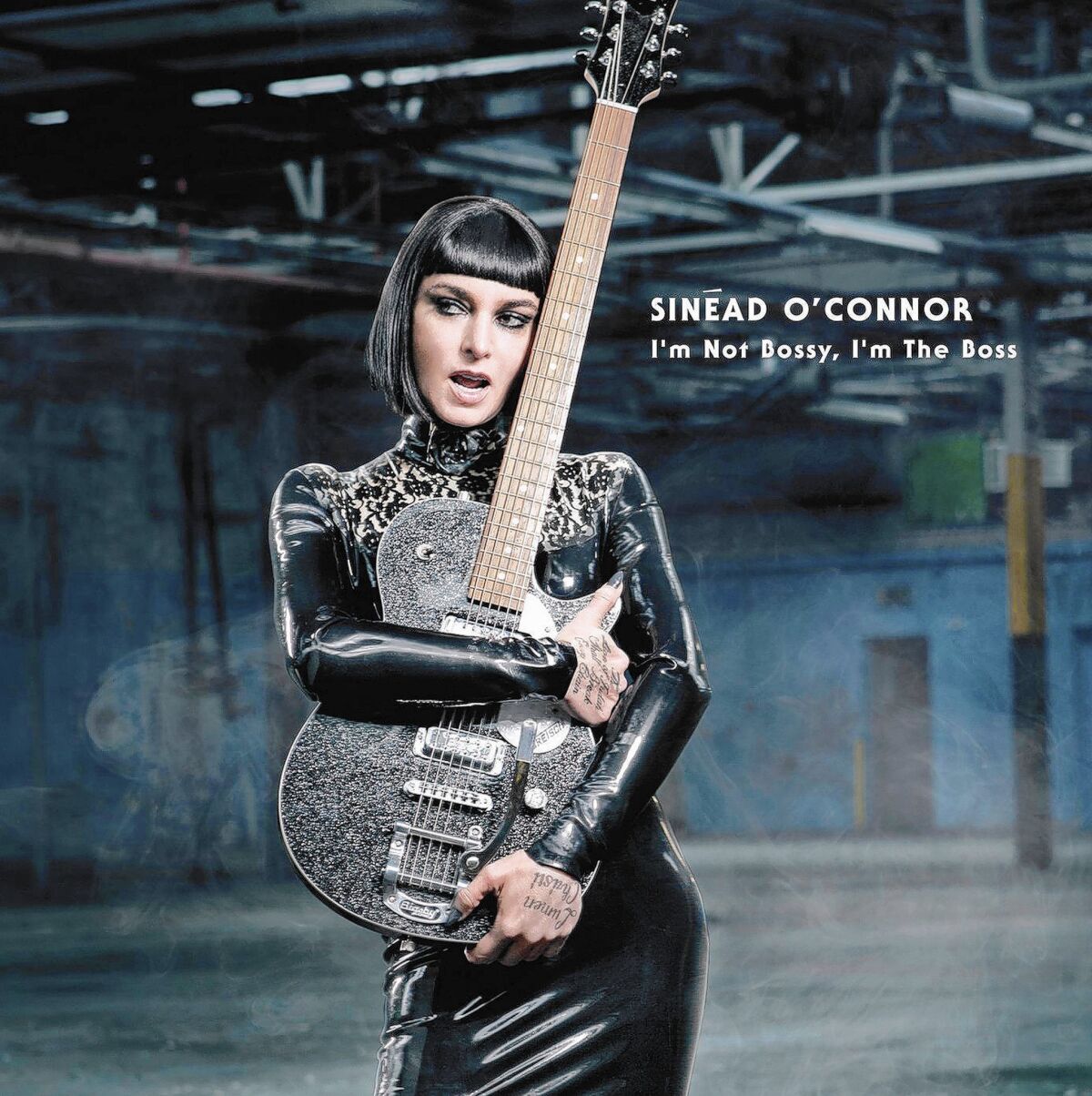

With her haunting voice, shaved head and sharp tongue, O’Connor remained a sentinel over her own sexuality, frequently subverting it so it wouldn’t “cheapen” her creative work. Occasionally, though, she played it up as needed, as was the case with her black-latex-clad cover art for her 10th album, 2014’s “I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss.”

Sinéad O’Connor’s “I’m Not Bossy, I’m The Boss.”

(Nettwerk Records)

Though musically respected, she often drew the ire of her peers. She pitted herself against Arsenio Hall in a defamation lawsuit that accused him of supplying Prince with drugs, called out Miley Cyrus in 2013 in an open letter telling her to stop being “prostituted” by the music industry, and vilified reality star Kim Kardashian in 2015 when she appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone — declaring it the death of rock and roll.

Meanwhile, her demons surfaced frequently on social media, raising concerns about her mental health and well-being. In interviews, she said she had attempted suicide and suffered from depression and PTSD.

“When you admit that you are anything that could be mistakenly, or otherwise, perceived as ‘mentally ill,’ you know that you are going to get treated like dirt, so you don’t go tell anybody,” she told Sky News. “That’s why people die.”

Born Dec. 8, 1966, in the Dublin suburb of Glenageary, O’Connor was the the third of five children. Her father John, an engineer-turned-lawyer, and her mother Marie’s marriage was troubled and O’Connor often spoke of growing up in an abusive household. Her parents separated when she was 8.

Adrift and rebellious, O’Connor was expelled from Catholic school and began shoplifting, just for something to do, she later explained. She ended up in reform school.

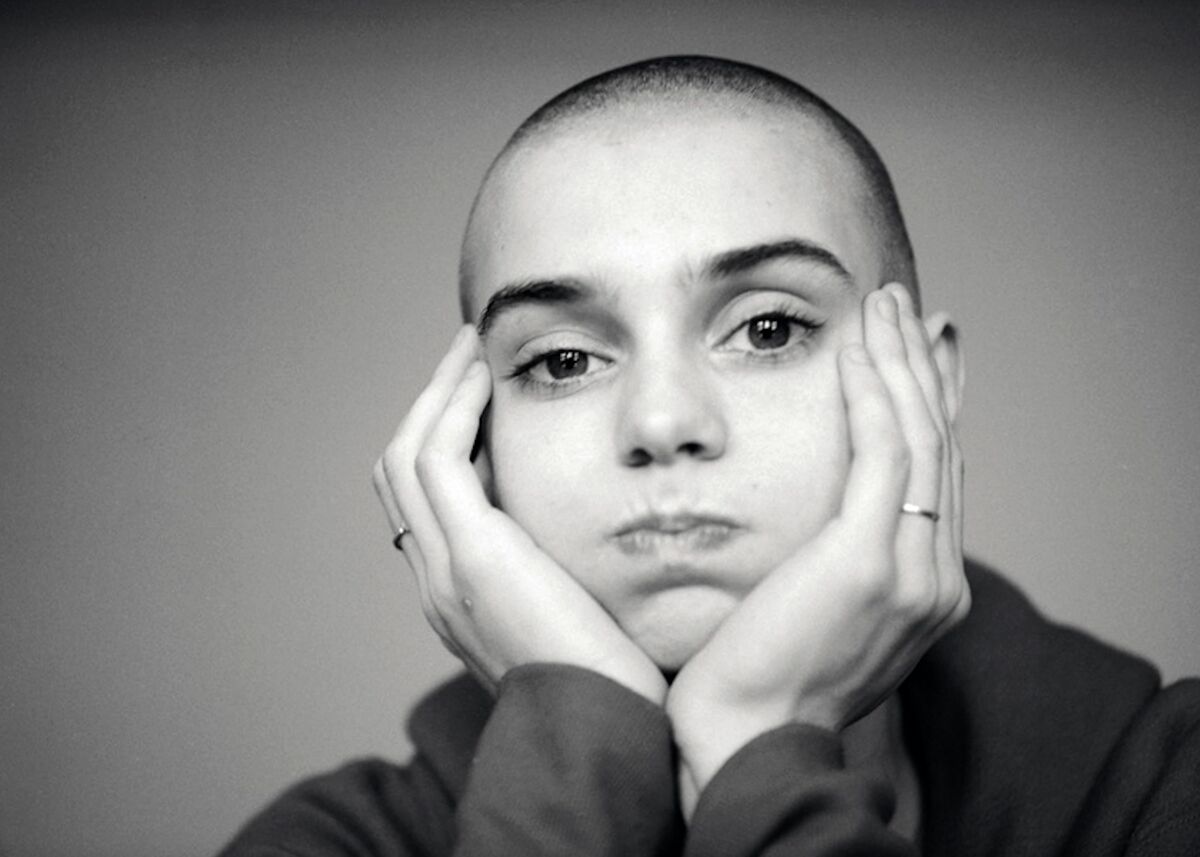

Sinéad O’Connor in 1988, as seen in “Nothing Compares” directed by Kathryn Ferguson.

(Andrew Catlin / Showtime)

At 16, she was discovered while singing at a wedding and later studied music. That hopeful glimmer at a future away from Dublin was seemingly snuffed out when her mother, the main supporter of her musical career, died in a car accident in 1985.

“I just felt like there was nothing left. I was like suicidally depressed. I wanted to self-destruct, which for me is smoking my brains out. I would go out and buy 60 cigarettes and smoke the whole lot just because I knew it was really bad for me,” she told The Times.

Her ticket out of Dublin essentially fell into her lap. She was singing in a local club with a failing funk band when she was spotted by Nigel Grainge, London’s Ensign Records founder. He signed her based on one ragged performance.

She collaborated with U2’s guitarist The Edge on “Heroine,” a song from a film score he was working on and then holed up in an apartment in southeast London, trying to write songs, certain her label would drop her any day.

Her first recording sessions were a disaster. She was pregnant, her singing was “embarrassingly bad” and the producer the label had sent her watched as his dreams of turning her into a modern-day Grace Slick crumbled.

So O’Connor took over as producer herself.

Her debut album “The Lion and the Cobra,” was a breakout hit that charted for six months. The single “Mandinka” topped the dance chart, and a version of the LP cut “I Want Your (Hands on Me),” revised as a duet with female rapper M.C. Lyte, kept her MTV profile high.

The album bubbled with invention and personality. In a review, The Times said it had a “timeless, ancient quality and a contemporary sheen — a mystical whiff of her Celtic roots along with nods to ‘80s hard rock and funk.” The album earned O’Connor her first Grammy for female rock vocal performance.

She set out for Los Angeles hoping to launch the acting career she thought about since watching Barbra Streisand movies with her mother. Instead, she emerged as one of 1988’s hottest new pop-music arrivals.

O’Connor made her local debut at the Wiltern Theatre in 1988 at 21. She burst on the scene as an odd-looking provocateur, dressed in an ice-skater skirt and combat boots. Her skinhead and powerful voice drew immediate attention. At the time, she claimed she shaved her head because she was bored with how she looked. Later, she claimed she did it to turn off frisky record executives.

“It was quite important to make myself as unattractive as I possibly could and I’m comfortable with that,” she told Oprah Winfrey.

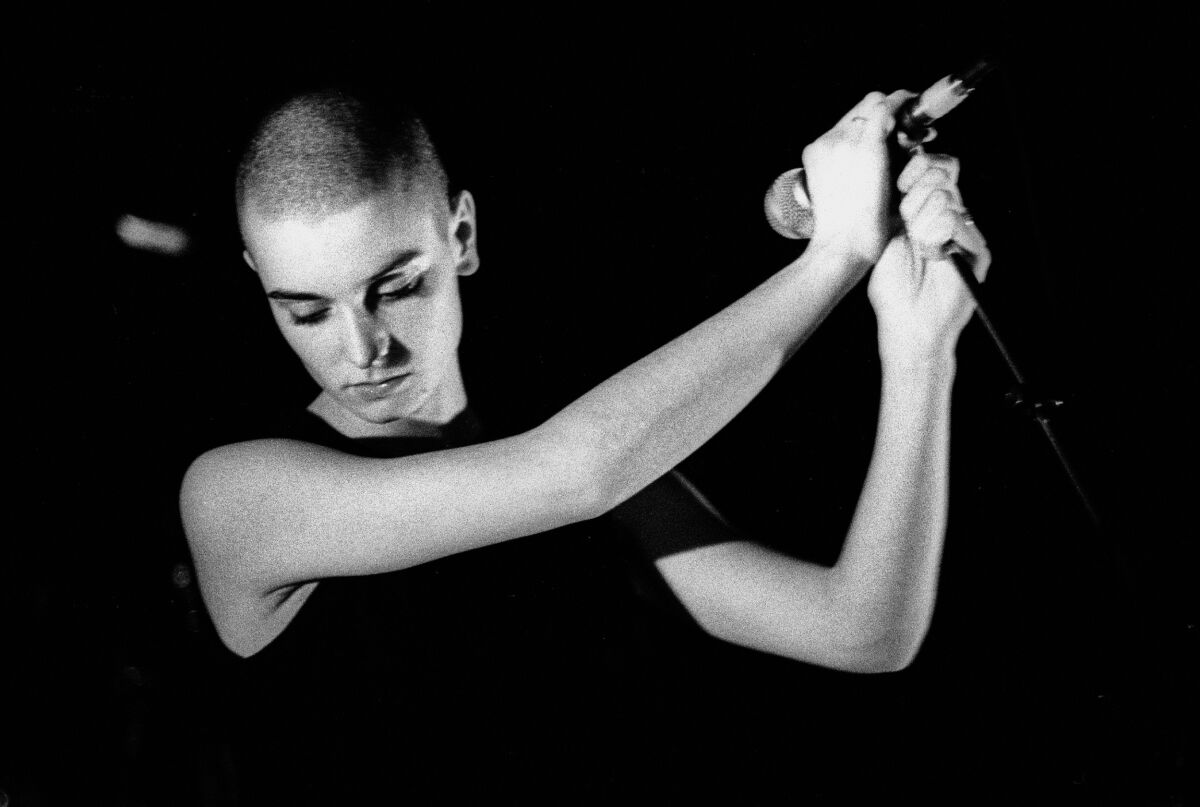

Sinéad O’Connor performs at Paradiso in Amsterdam in March 1988.

(Paul Bergen / Redferns via Getty Images)

Her second record, “I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got,” became an international sensation. Her cover of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” was her first No. 1 hit and she was nominated for four Grammy Awards. Rolling Stone named her Artist of the Year.

But her tangled personal life and erratic behavior often shadowed her talents.

She claimed Prince “summoned” her to his home in 2014, telling her he didn’t like that she swore during interviews. When she responded by telling him to “f— off,” a wild car and foot chase in the Hollywood Hills ensued, she claimed.

O’Connor was married four times, first to producer John Reynolds, then to journalist Nick Sommerlad, musician Steve Cooney and finally Barry Herridge, a therapist. She had two children with two of her husbands, and two more with boyfriends.

She had a three-year battle with former boyfriend John Waters over custody of their daughter that ended in March 1999 when she took an overdose of Valium in an apparent suicide effort and then agreed to let the 3-year-old girl, Roisin, live with Waters.

O’Connor said she canceled her “How About I Be Me (And You Be You)?” tour in 2012 because of concerns over her mental well-being. A family fallout also preceded an apparent November 2015 suicide attempt that she announced on Facebook.

“I have taken an overdose,” she wrote. “There is no other way to get respect. I am not at home, I’m at a hotel, somewhere in Ireland, under another name. If I wasn’t posting this, my kids and family wouldn’t even find out.”

Sinéad O’Connor performs at the El Rey Theatre in Los Angeles on Feb. 20, 2012.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

She eventually was located in Dublin after authorities were alerted to the threat, police said at the time. Similar incidents played out in 2017, when O’Connor was hospitalized after posting a suicidal Facebook video in which she urged her family to contact her.

O’Connor announced her conversion to Islam in 2018, tweeting that “this is the natural conclusion of any intelligent theologian’s journey. All scripture study leads to Islam.”

She also changed her name to Shuhada’, which means “one who bears witness” and martyr in Arabic. That name change followed an earlier one. She previously took the name Magda Davitt, according to CNN.

In 2020, she canceled several 2021 shows upon revealing that she would be entering a one-year treatment program for trauma and addiction.

In 2021, she published a memoir, “Rememberings.” Though she had vowed it would be a tell-all book packed with “sexual dirt,” the book was introspective, poignant and very much a cautionary tale.

Shortly after she announced a 2022 tour of the U.S. and Ireland, her 17-year-old son Shane committed suicide and — days later — she alarmed fans when she tweeted “I’ve decided to follow my son.” She later went to a hospital and asked for help.

O’Connor told The Times that through her professional life she often felt isolated by her fame and notoriety.

“I think the most crushing thing is the isolation that comes from being a person who is not seen as an ordinary human being, but someone on whom other people’s expectations are placed.”

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.